In doing research for a new book, I recently spent a Sunday reading Bank of England reports and obscure presentations from the early 2010s – a highly recommended activity if you don’t want any follow-up questions when someone asks “what have you been up to today?”

I’ve previously written about Quantitative Easing (QE) here, which is – in a nutshell – a fancy word for the Bank of England creating money out of thin air. It’s a policy that had never been used in the UK before 2008, but has become a fixture of monetary policy since it was first used to give the economy a boost in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

As I pointed out in that article, one of its effects has been the extreme growth in asset prices over the last decade:

- The value of the FTSE All-Share has almost doubled

- House prices are up up 63%

- Gilts are up by 80%

- Gold is up by 180%

What I didn’t realise is that the Bank of England knew full well that asset price inflation would be not just a consequence of QE, but a core part of the mechanism.

Asset price inflation as a feature, not a bug

The stated purpose of QE was to help maintain the Bank of England’s inflation target of 2% (as measured by the Consumer Price Index, or CPI), at a time when they thought it looked likely to under-shoot over the medium term. Having already cut the base rate of interest to almost nothing (which is the normal way of giving the economy a boost and getting inflation going), the Bank needed a new tool – and QE was it.

In theory, adding a load of extra money into the economy (which is what QE does) should produce inflation because you suddenly have more money chasing the same amount of goods and services. However, the mechanism of QE (which we don’t need to get bogged down in now, but I cover it here) meant that the new money ended up chasing financial assets rather than goods and services in the “real” economy.

Yet asset prices aren’t included in CPI inflation figures – so even if the price of all assets goes up a bajillion percent, it doesn’t help the Bank of England achieve its target.

Because QE had never been used prior to 2008 and operates through some pretty convoluted channels, I assumed it just hadn’t worked out quite how the Bank of England intended: they were shooting for consumer price inflation, but ended up with asset price inflation instead.

But no!

The Quarterly Bulletin from Q2 2009 states:

“Purchases of assets financed by central bank money should push up the prices of assets”

And goes on to say:

“[as a result of the QE process] Households and companies may be encouraged to switch into other types of asset [rather than gilts] in search of a higher return. That would push up on other asset prices as well.”

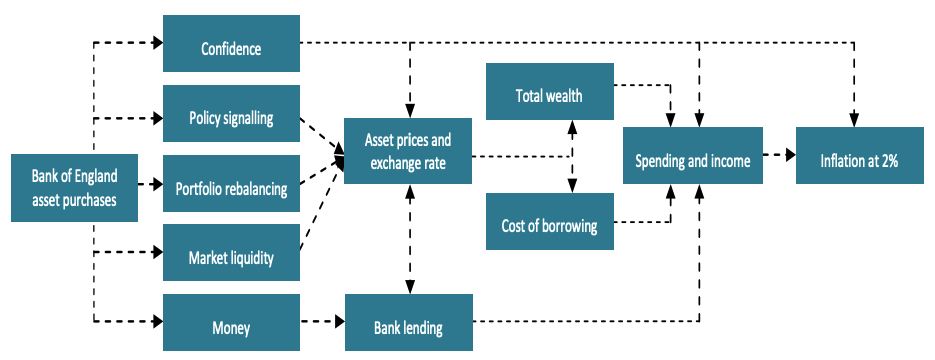

The intention seemed to be that boosting asset prices would make people wealthier, which would make them more inclined to spend, which would get the economy moving and produce the 2% inflation the Bank was shooting for. That mechanism is depicted in this handy flowchart from a conference presentation given in 2013:

So, did this work?

We know there was asset price inflation, but did it “trickle down” into consumer activity in the way the Bank intended?

It’s impossible to say for sure, because you can’t run a version of the economy where everything was exactly the same except QE didn’t happen. However, the Bank of England estimates that the first £375bn of new money it created with QE led to a 1.5% to 2% growth in GDP. If you do the maths, that means it created £23bn to £28bn of extra spending.

The House of Lords’ Economic Affairs Select Committee wasn’t convinced in July 2021, when they wrote:

We conclude, on balance, that the evidence shows quantitative easing has had limited impact on growth and aggregate demand over the last decade. To stimulate economic growth and aggregate demand, quantitative easing is reliant on a series of transmission mechanisms that operate primarily in and through financial markets. There is limited evidence to suggest that these increase bank lending or investment, or boost consumer spending by wealthy asset holders.

Who benefits from asset price inflation?

So we can say QE probably caused some GDP growth that would have helped juice up inflation, but it required printing a lot of money to do so.

Clearly, this policy benefits the owners of assets – and disadvantages those who would like to own assets but can’t afford to. Asset owners see a boost in the value of what they already own – which they can often borrow against to buy more. The act of them buying more raises asset prices even further…taking them further out of reach of those who don’t own them yet.

So who are the owners of assets?

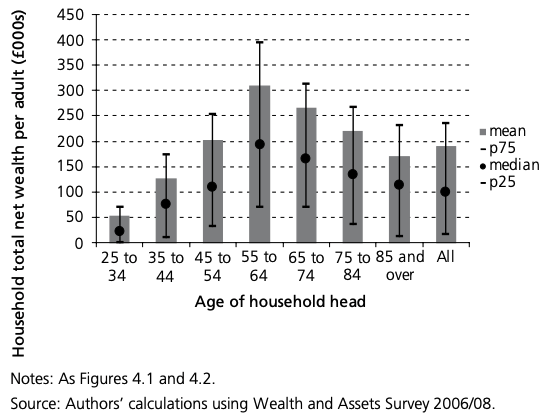

According to this chart (taken from this report) based on data from shortly before QE got underway, older people tend to have far higher net assets than younger people:

This isn’t surprising (it would be weird if on average someone with 20+ years in the workforce hadn’t accumulated more assets than someone who’d just finished education), but still – it’s clear that policies that advantage asset owners will disproportionately benefit older people at the expense of younger ones. Not to mention educated people at the expense of the less educated, and people living in the South East at the expense of those living elsewhere, as both these groups also have higher net wealth on average.

To be balanced, some analyses have found that despite this, QE has reduced inequality by boosting levels of employment and wages – which disproportionately effects those towards the bottom of the wealth distribution.

But the House of Lords’ committee remained unconvinced, saying:

On balance, we conclude that the evidence shows that quantitative easing has exacerbated wealth inequalities…The Bank has not adequately engaged with debate about the trade-offs created by sustained quantitative easing. We heard that it has been “defensive” about the extent to which quantitative easing has exacerbated inequalities

What to make of all this?

Well, you could say the first takeaway is not to be a slouch and be sure to read Bank of England reports as soon as they come out rather than a decade later: if I’d done so, I would’ve loaded up on assets far more aggressively than I did.

But less selfishly, it seems to me that if you were trying to exacerbate generational inequality, you’d struggle to find a more effective way of doing it than QE. And this has happened via a mechanism that was entirely intentional and foreseen, not an unfortunate side-effect.

Keep that in mind next time you see a politician wringing their hands about how terribly difficult things are for young people, and how something must be done.

As always, a great read Rob Dix, thank you for taking the time to (a) read the reports & (b) summarise for those like me that haven’t read them.

Have a relaxing weekend, I look forward to the launch of Portfolio and good luck with your Horwich purchase (I know the area well).

Thank you Glyn!